The Surprising History of the 270 Winchester

What 100-year-old rifle cartridge shoots fast, far, and flat, recoils mildly, and terminates everything from jackrabbits to grizzlies? The 270 Winchester.

When officially released in 1925, the 270 delivered impressive muzzle velocity and reach, two attributes hunters were yet to fully appreciate, mainly because telescopic sights were uncommon. Those with good enough eyes and technique were surprised and undoubtedly delighted to discover they could hold for the center of a deer’s vitals at any distance out to about 300 yards and strike a killing blow. Revolutionary.

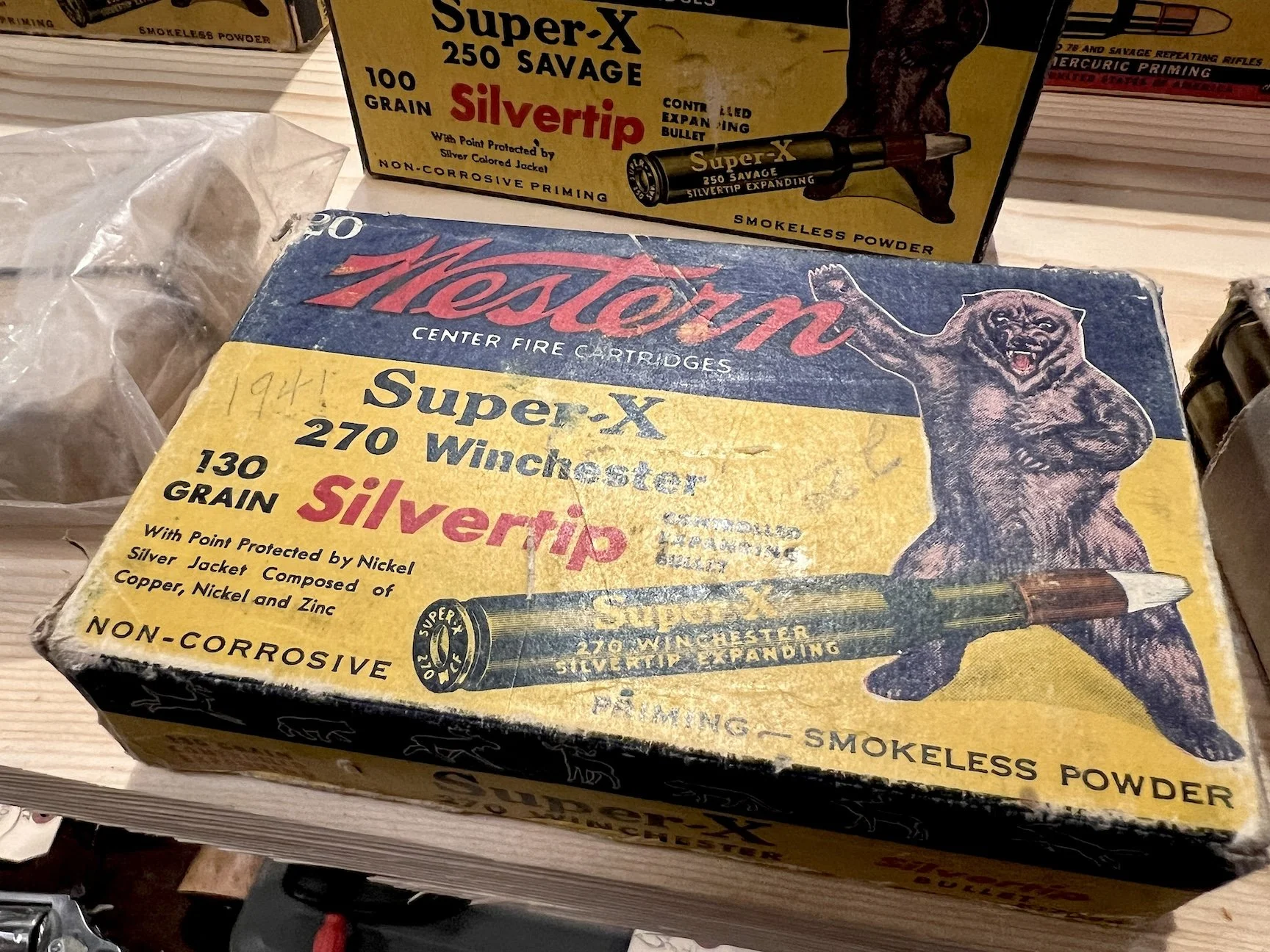

This is the Western (Winchester) ammunition and bullet that helped make the 270 Winchester cartridge’s reputation.

Today, despite its advanced age, the all-American 270 Winchester remains one of the world’s best “long range” hunting cartridges. And it’s still full of surprises. Thanks to 21st century bullets, powders, and rifle designs, it can now shoot faster and flatter than ever, deflect less in the wind, and drop more energy on target. Before we reveal how, let’s review some of this old hot-rod’s history.

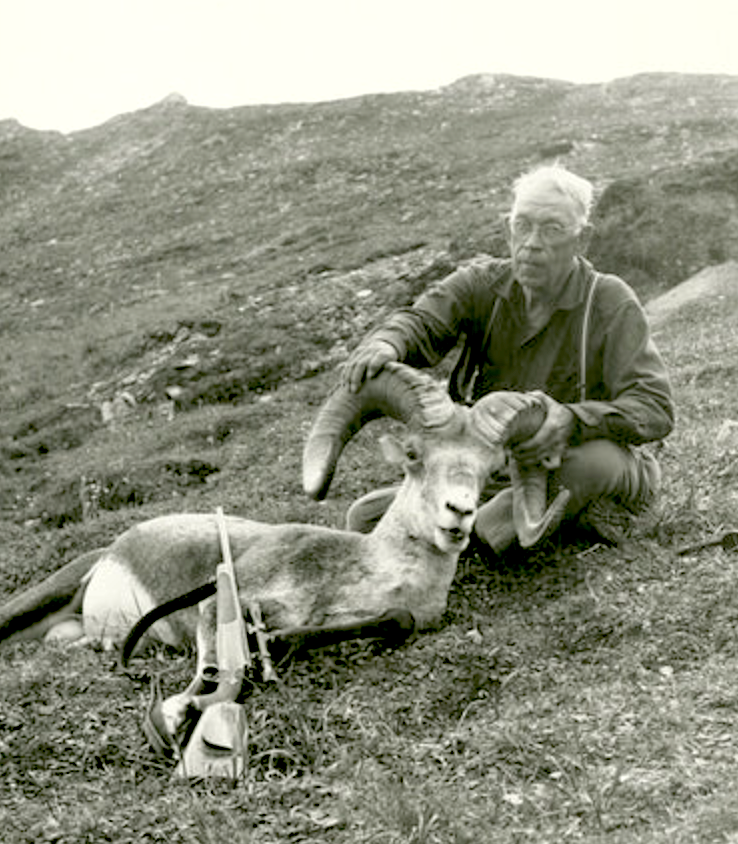

Gun and hunting writer Jack O’Connor was the 270 champion that brought it to prominence in the middle of the 20th century. He bought a Winchester Model 54 bolt-action chambered in 270 Winchester the first year it became available, 1925. When Winchester modified the M54 to make the Model 70, O’Connor was one of the first to upgrade to it. Thereafter he hunted widely with two or three custom-stocked M70s chambered 270 Winchester. O’Connor cut his 270 teeth shooting jackrabbits and coyotes, then desert mule deer and the little Coues whitetails before taking on desert sheep, whitetails, bighorns, Dall sheep, caribou, elk, moose and, if I’m not mistaken, grizzlies. What made his exploits important for 270 Winchester sales was that he told everyone about them each month in Outdoor Life magazine.

Jack O’Connor started shooting the 270 Winchester as a young man and continued well into his senior years. Here he is with one of his custom-stocked M70s and a Stone sheep.

While many firearms aficionados know that the M54, not the M70, was first rifle chambered for the 270 Winchester, few know that a predecessor to the M54, the little-known Model 51 “Imperial,” was chambered for the 270 BEFORE 1925, but under a different name. Here’s how that happened.

Right after WWI, Winchester gun designer Thomas C. Johnson began engineering a bolt-action rifle that would compete with the high-quality sporting models from Germany and England. Many on Winchester’s board of directors scoffed at bolt-actions, thinking them inferior to lever-actions, a passing fad, perhaps. But they did allow Johnson’s Model 51 bolt-action to go into limited production in the Gunsmith Shop in 1919. Only 24 were built before the experiment was shut down in February of 1920. Most M51s were chambered 30-06 or 35 Whelen, but a few were chambered for the 27-caliber. That was, apparently, the only moniker Winchester gave it at the time. Just 27-cal. engraved on the barrel.

The rare Winchester Model 51 of 1919. Note the dog-legged bolt handle, steeply dropping comb, and Schnable fore-end. Foreshadowing of the Model 70 Featherweight to come.

A year after Winchester dropped the M51, Remington’s new Model 30 bolt action hit the market and began capturing market share. By 1924 Winchester reversed course, announcing the Model 54, an evolved version of the M51. To sweeten the deal, they simultaneously released a “new” cartridge chambered in it – the 270 Winchester. A more memorable name than 27-caliber, I think.

With the new rifle and new 270 Winchester cartridge, a star was born.

Today most hunters know the 270 Win. is basically the 30-06 necked down. But the 270 case has a slightly longer neck -- the exact length of the 30-03 military cartridge of 1903. This was what the U.S. military had come up with to keep pace with European military rounds such as the 6.5x55 Swede, 7x57mm Mauser and 8x57 Mauser. Hide bound and traditional as always, the U.S. military brass saddled their new 30-03 with a 220-grain round nose bullet. Within three years they realized the new, lighter, “spitzer” shaped bullets the Germans were using on their 8x57 JS cartridge (7.92x57mm) were more efficient. So, the 30-03 case was modified by shaving 0.046” off the neck and fitting it with 150-grain spire point bullets to create the long-lived 30-06.

Because the 270 case has this same longer neck, many insist the 30-03 was the parent case. Others note that when 30-06 brass is squeezed through a 270 Winchester die, the displaced brass flows forward to reach the 30-03 length.

Standing beside the 30-06 (far left), the 270 Winchester shows its pedigree. Notice its neck is a smidge longer then the 30-06’s, which leads many to claim the 270’s parent case was the old 30-03 military cartridge. Regardless, the 270 Winchester ranks with the rest of these (30-30, 308 Win. and 243 Win.) as one of the most popular and successful deer cartridges in North America.

More important than “which was the parent case” is the result: the 270 cartridge drove 130-grain bullets 3,140 fps. Or at least that’s what Winchester advertised from a 24-inch barrel. The slimmer diameter of the .277” projectile, matched with that velocity, resulted in a flatter trajectory than the 30-06 provided with not just 150-grain, but even 130-grain bullets. The 30-06 can drive a 130-grain .308 bullet a bit faster than a 270 can push its 130-grain, due to the increased diameter of the .308 bullet base more effectively utilizing chamber/bore pressure. The narrower .277 bullet, however, encounters less air drag, so it traces a flatter trajectory curve and carries more energy downrange.

Despite these advantages, 270 sales lagged behind the 30-06 for many years. But once reliable scopes appeared after WW II, the 270 began catching fire. Mr. O’Connor’s stories fanned the flames. By the 1950s the 270 had become the long-range darling for deer, pronghorn, and sheep hunters.

Elk hunters, on the other hand, demanded a heavier bullet, so Winchester gave them a 150-grain at 2,850 fps. Elk, moose, and bear hunters appreciated the increased close-range energy and momentum for deeper penetration, but many reportedly balked at the lower velocity. Winchester next released a 100- grain hollow point varmint load streaking about 3,500 fps. Plenty of speed in this one, but not enough mass. The original 130-grain remained the hands down favorite.

While the 270 Winchester can be and has been loaded with bullets from 90-grains to 170-grains, most factory ammo today is topped by a 130-, 140-, or 150-grain projectile.

From the get-go the 270’s twist rate has been 1-10”. This proved ideal for the 130-grain and adequate for the 150-grain bullets of the era, but too slow for anything longer unless a rather short, 160-grain round nose. Over the years a few 170-grains were offered handloaders, but they may have been shooting faster rifling twists. Perhaps the best compromise bullets are the 140-grain boat tail spire points.

The advent of long, aerodynamically efficient bullets in 6.5mm and 7mm cartridges in the past 20 years has put a bit of a crimp in 270 Winchester sales. “Wimpy” cartridges such as the 6.5 Creedmoor lose the muzzle velocity race to the 270, but at some distance beyond 350 or 400 yards they catch up and pass the old speed champ. This is all due to the elevated ballistic coefficient of the new bullets. Of course, .277” bullets can be made equally efficient, but this makes them too long to stabilize in a 10” twist. One answer to this is Winchester’s 6.8mm Western, a short-fat round that is what the older 270 WSM probably should have been in the first place.

The short, fat 6.8 Western (center, beside 270 Winchester) is the 21st century answer to the old standard. Like the other “modern” cartridges shown here beside their 20th century predecessors, the 6.8 Western accommodates long, heavy, ballistically efficient bullets.

The other answer is simply a faster twist barrel chambered for the standard 270 Winchester. Browning did this with one of its X-Bolt models. Joseph von Benedict and I tested one of these with some of today’s longest .277 bullets and achieved safe-pressure velocities matching and even slightly besting the 6.8 Western. In addition to the 1-7.5” twist, the Browning’s barrel was throated long and its magazine opened to 3.6 inches. That’s full magnum length, enabling the long bullets to be seated well out, leaving plenty of powder space for impressive velocities at what appear to be quiet safe chamber pressures. As I recall, Joseph and I burned 61.2 grains of H1000 with 175-gr. Sierra GameKings seated to 3.55” COAL. The base of the boat tail barely reached below the case shoulder. MV hit 2,950 fps or so.

Traditional 130-gr. 270 Win. load beside long bullets. Note how much longer the cartridge would have to be if bullet bases projected no deeper than the shoulder/body junction of the case. Handloaders can do this is their rifle has a long enough magazine and throat plus rifling twist of 7.5” or 8”.

Fun and enlightening though that project was, Joseph and I both agree that such performance is hardly necessary to keep the 270 Winchester in the limelight. With today’s controlled expansion bullets at traditional MVs from traditional rifles topped with a modern scope like the Maven RS 1.2 2.5-15x44 coupled with a laser rangefinder, a 270 Winchester built in 1950 can still deliver the mail to distances at which most of us have no business stretching!

Speaking of Maven scopes, that company was kind enough to provide us with all the scopes used in filming our 270 Week videos.

Landon shoots a Rifles, Inc. super lightweight rifle fitted with what I consider an ideal scope for the roaming, hiking, stalking, all-around hunter. It’s a Maven CRS.1 3-12x40 that weighs just 14.2 ounces. If you can’t take your deer, sheep, or elk with this scope out to all sensible shooting distances, you aren’t trying.

We found those optical instruments impressively solid, tight, functional, bright, and sharp, indications that Maven is using not only top-quality glass perfectly ground, but the anti-reflection lens coatings critical for maximizing light transmission. Whenever you are examining or comparing scopes, make it a point to aim toward the morning or evening sun. Not enough to put Old Sol in your view, but enough to get its rays on the objective lens while you look for things in the shadows. If the view is hazy or muddy, keep looking for another scope. Haze is a product of uncontrolled light waves bouncing from lens to lens inside the scope. Anti-reflection coatings control this and lots of those coatings nearly eliminate it. We were impressed with our views through the Mavens. And those scopes dialed as advertised, returned to zero, and held zero throughout our testing. I won’t pretend to tell you which scope is best for you, but I’m happy to tell you whenever I stumble upon a scope that works well for me. You make up your own mind. Maven headquarters are in Wyoming.

Tate works with a new Maven RS.5 4-24×50mm scope that performed perfectly for us on a variety of rifles. Bright, tight, sharp, and smooth with accurate reticle movement. The skeletonized action is a Stiller/Horizon Wombat weighing just 23 ounces.

To put the 270 Winchester in perspective, consider that in the year it appeared (officially), commercial radio was just five years old. Radios wouldn’t be fitted into automobiles for another five years. Televisions didn’t exist. Jet airplanes were still 20 years in the future. We’ve come a long way, baby, and the 270 Winchester had ridden with us. It’s ready and able to go another 100 years.